Knowledge diffusion (scientific audiences)

2022

The Aegean Palaeolithic research agenda, N. Galanidou, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads, Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

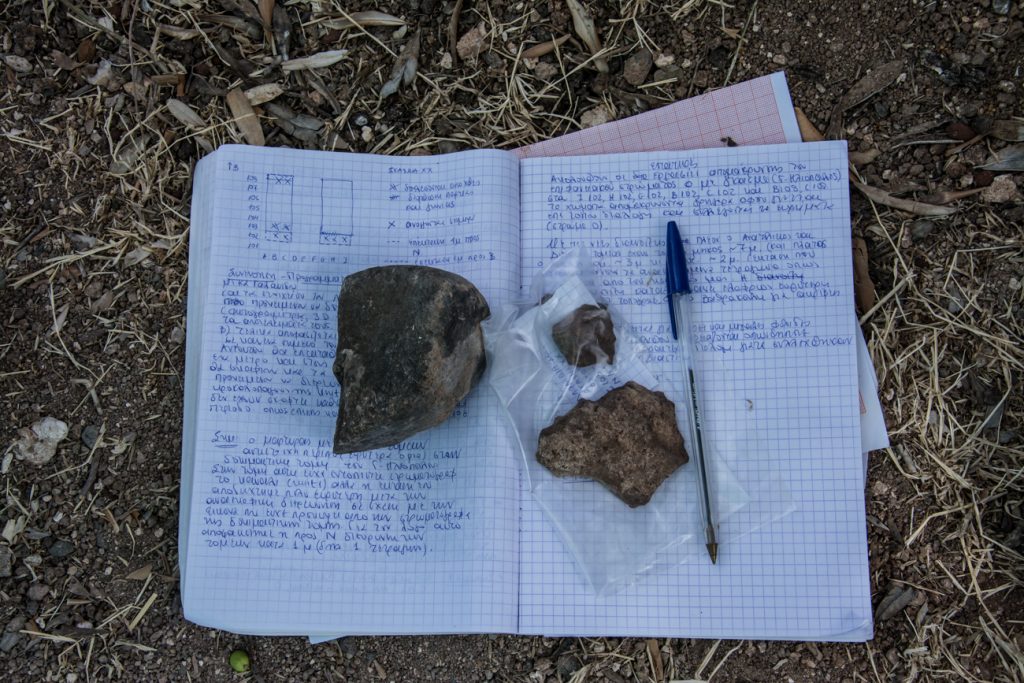

Digging, mapping, profiling, trenching, and sampling: archaeological field strategies for investigating the Acheulean Rodafnidia, Lesbos,N. Galanidou, J. McNabb, P. Tsakanikou, E. Karkazi, N. Soulakelis, C. Vasilakos, E.E. Papadopoulou, G. Iliopoulos, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

The Acheulean site of Rodafnidia: geology, stratigraphy and chronology, G. Iliopoulos, I. Alexopoulos, P. Papadopoulou, A. Zelilidis, S. Dilalos. N. Voulgaris, A. Biggin, L.J. Arnold, N. Taffin. N. Galanidou, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

Lithic Raw Material Economy and Provenance at the Acheulean site of Rodafnidia, Lesbos, E. Karkazi and A. Magganas, N. Galanidou, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

A 3D geometric morphometric shape analysis of the Acheulean Large Cutting Tools from Lesbos, G. Herzlinger, N. Galanidou, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

The Acheulean site of Rodafnidia: detailed sedimentological analyses, N. Bourli, G. Iliopoulos, N. Galanidou, A. Zelilidis, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

Following the water: palaeocurrent directions of the Middle Pleistocene fluvial network of Rodafnidia, Lisvori, N. Bourli, G. Iliopoulos, P. Papadopoulou, N. Galanidou, A. Maravalis, A. Zelilidis, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

The palaeoenvironment of the Acheulean site of Rodafnidia: the microfossil record, P. Papadopoulou, K. Vasileiadou, M. Kolendrianou, G. Iliopoulos, N. Galanidou, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

The Kamara and Vathy Lagkadi Palaeolithic sites, Lisvori: geology, stratigraphy and finds,N. Galanidou, P. Tsakanikou, G. Iliopoulos, P. Papadopoulou, L.J. Arnold, A. Zelilidis, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

Soil resources as indicators for affordances at the Acheulean site of Rodafnidia: a geoedaphic approach, S. Kübler, P. Tsakanikou, G. Iliopoulos, N. Galanidou, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

Plio-Quaternary palaeogeographic evolution of central south Lesbos: implications for Palaeolithic Archaeology, S. Sotiropoulou, M. Kalaitzis, D. Sakellariou, E. Skourtsos, C. Kranis, T. Hasiotis, N. Galanidou, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads. Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022.

The Villafranchian fauna of Vatera, Lesbos, Greece, Athanassiou, G. Lyras, A.A.E. van der Geer, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads, Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022

Reassessing the biogeographical role of the Aegean region during the Early and Middle Pleistocene: an affordance-based modelling approach, P. Tsakanikou, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads, Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022

The Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads: round table discussion

Coordinators: P. Chauhan, J.A.J. Gowlett, Ν. Galanidou, A. Ollé, H. Taşkiran, Aegean Acheulean at the Eurasian crossroads, Hominin settlement in Eurasia and Africa, University of Crete, The Museum of Industrial Olive-Oil Production, Lesbos, June 2022

Palaeolithic Heritage, tourism and agricultural communities in Greece, G. Beka, Archaeology, Local Societies and Tourism, University of Crete, Rethymno, January 2021

2021

Archaeology and everyday life. Public archaeology in the forefront, G. Beka, N. Galanidou, Material Culture, Archaeology and Tourism: From archaeological replicas to travel materialities and touristic souvenirs, University of Crete, Rethymno, October 2021

Exploring the early settlement in the Aegean Basin: Palaeolithic Lesbos, N. Galanidou, The University of Crete Archaeological Fieldwork: Research and Education, University of Crete, Rethymno, November 2021

The Aegean Acheulean: A view from Rodafnidia on Lesbos, N. Galanidou, G. Iliopoulos P. Tsakanikou, E. Karkazi, P. Papadopoulou, N. Bourli, A. Zellilidis, A. Magganas, L. Arnold., XIX Congress of the UISPP (International Union of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences-Union Internationale des Sciences Préhistoriques et Protohistoriques), Meknès, September 2021

Gender in Public Archaeology: Feminist discourses in rural Lesbos, G. Beka, N. Galanidou, European Association of Archaeologists – EAA 27th Annual Meeting, Kiel, September 2021

Refloating the Aegean Lost Dryland: An Affordance-Based GIS Approach to Explore the Interaction Between Hominins and the Palaeolandscape, P. Tsakanikou, European Association of Archaeologists – EAA 27th Annual Meeting, Kiel, September 2021.

The Palaeolithic Lesbos Thesaurus and Database: Digital recording, documentation and management of the Acheulean artifacts and field research, N. Galanidou, P. Zervoudakis, L. Harami, P. Tsakanikou, E. Karkazi, G. Beka, A. Magganas, day meeting Apollonis, Institute of Informatics, FORTH, September 2021.

Building the digital communication of Palaeolithic Lesbos with the public, N. Galanidou, G. Beka, Digital communication in culture and tourism: The Greek case study, International University of Greece, Digital Marketing MA course, June 2021

The Aegean dryland: The lost ‘middle route’ to Europe? Assessing implications for hominin movement and occupation during the Lower Palaeolithic, P. Tsakanikou, CAHO Seminar Series 2020-2021, Centre for the Archaeology of Human Origins, University of Southampton, UK, February 2021

2020

The Acheulean archaeology of Lesbos, Greece and the Aegean corridors connecting east and west Eurasia, N. Galanidou, Down Ancient Trails: Archaeology Forum, Sharma Center for Heritage Education, India, June 2020

2019

Archaeological research and insular societies in the Aegean, G. Beka, N. Galanidou, Archaeological Dialogues, 5th Meeting – Thalasso-Geographies: Sea Routes, Flows, Networks, University of Thessaly, Volos, May 2019

Local Communities and Heritage Management: Ethnoarchaeology as Agency, G. Beka, P. Zervoudakis, Sense and Sustainability International Conference on Archaeology and Tourism, Zagreb, May 2019

2018

Memories, Space and Palaeolithic Archaeology Μνήμες: preliminary results of an ethnographic approach, G. Beka, 24th Pan-Hellenic Postgraduate Intensive Seminar -Conference: Methodological Issues in Social Sciences Research, University of Crete, November 2018

Acheuleans in the Aegean Neanderthals in the Ionian Sea: A view from SE Europe, N. Galanidou, The Prehistoric Society Europa Conference 2018 – Coastal Archaeology in Prehistory, A conference celebrating the achievements of Professor Geoff Bailey in the field of European prehistory, University of York, UK, June 2018

Middle Pleistocene raw- material procurement and use in the Aegean: a view from the Acheulean of Lesbos, N. Galanidou, E. Karkazi, A. Magganas, UISPP, XVIII Colloque, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris, France, June 2018

Palaeolithic archaeology and submerged landscapes in Greece: The current state of the art, N. Galanidou, A. Zavitsanou, P. Tsakanikou, D. Sakellariou, UISPP, XVIII Colloque, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris, France, June 2018

2017

The Middle Pleistocene archaeology of Lesbos, N. Galanidou, Quaternary Interglacials, 3ο International Workshop: Interglacials of the 41kyr-world and the Middle Pleistocene Transition, Molivos, Lesbos, August 2017

2016

Sea and Land during the Tertiary and the archaeology of early dispersals, N. Galanidou, 3rd International Geo-Cultural Symposium “Samaria 2016”, Centre of Mediterranean Architecture, Chania, May 2016

Lesvos half million years ago: archaeological evidence from Rodafnidia, Lisvori, N. Galanidou, Palaeolithic Seminar, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, March 2016

2015

Towards an insular Palaeolithic Archaeology. Sea and Land during the Pleistocene. Ν. Galanidou, Island Interdisciplinary Workshop: Islands and Islanders in the Aegean and the Mediterranean. Island worlds during a long geo-cultural spectrum, in honour of Émile Kolodny, University of Crete, Rethymno, December 2015

Lower Palaeolithic Rodafnidia: lithic raw material provenance and petrography, E. Karkazi, A. Magganas, A. Katerinopoulos, G. Iliopoulos, N. Galanidou, 2nd International Geo-Cultural Symposium “Sigri 2015”, University of the Aegean, Lesbos, June 2015

Archaeological discovery on the Aegean shelf, N. Galanidou, International European Maritime Day Conference – Maritime Cultural Heritage and Blue Growth: What’s the Connection, Megaron the Athens Concert Hall, May 2015

Middle Pleistocene Hominids in Greece: a view from the Acheulean site of Rodafnidia on Lesvos, N. Galanidou, Seminar, British School at Athens, Athens, May 2015

Middle Pleistocene Hominins at the doorstep of Europe: The Acheulean Site of Rodafnidia on Lesvos, Greece, N. Galanidou, PalMeso Semimar, Dept. of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, UK, March 2015

Public engagement with the ancient world in Greece: Limitations and prospects, Ν. Galanidou, Material Cultures in Public Engagement: European Perspectives on public engagements with collections of the Ancient World, Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, UK, March 2015

Middle Pleistocene Hominins on the Eastern Doorstep of Europe: The Acheulean Site of Rodafnidia on Lesvos, Greece, N. Galanidou, The York Seminars, Dept. of Archaeology, University of York, UK, March 2015

2014

Τhe Acheulean site at Rodafnidia, Lisvori on Lesvos, Greece, Ν. Galanidou, European Acheuleans. Northern v. Southern Europe: Hominins, technical behaviour, chronological and environmental contexts, Natural History Museum Paris, France, November 2014

New Palaeolithic Research in the Aegean and Ionian Seas: Implications for Dispersal and Underwater Research, Ν. Galanidou, DISPERSE Project. Dynamic Landscapes, Coastal Environments and Human Dispersals, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, Anavyssos, November 2014

From Africa to the Aegean: The first human evidence from Greece, Ν. Galanidou, Darwin Monday, Natural History Museum, University of Crete, Heraklion, October 2014

Lower Palaeolithic research where Asia meets Europe: The Acheulean Rodafnidia on Lesvos, Greece, N. Galanidou, Seminar, Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, Natural History Museum Paris, France, September 2014

Cherts and prehistoric artifacts: first petrological results from new findings in Meganisi island, Lefkas and Rodafnidia, Lisvori, Lesvos, Greece, Α. Magganas, Ν. Galanidou, P. Xatzibaloglou, G. Iliopoulos, Α. Κaterinopoulos, International Symposium – Coastal Landscapes, Mining Activities & Preservation of Cultural Heritage, Milos, School of Geology and Geoenvironment, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, September 2014

The Quaternary Sea: Α linking thread in early human travels in the Aegean Basin, Ν. Galanidou, Archaeology of the Sea International Conference co-organised by the Greek Ministry of Culture, the Free University of Brussels (ULB) and the Catholic University of Leuven, complementing the Nautilus exhibition, Navigating Greece, Royal Museums Brussels, March 2014

2013

Pleistocene Submerged Landscapes and Palaeolithic Archaeology in the Tectonically Active Aegean Region, D. Sakellariou, Ν. Galanidou, Under the Sea: Archaeology and Palaeolandscapes, University of Szczecin, Poland, September 2013

Looking for the palaeolithic humans and hominins of the Aegean and Ionian Seas, Ν. Galanidou, Workshop. Archaeological research and training in the University of Crete. Methods, evidence, evaluations, perspectives, University of Crete, Rethymno, May 2013.

Looking the first inhabitants of the Aegean: the Palaeolithic excavation in Rodafnidia, Lisvori, Lesbos, Ν. Galanidou, Island Identities. The contribution of the Secretariat General for the Aegean and Island Policy in the research and promotion of the archipelagic cultures. Secretariat General for the Aegean and Island Policy, Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens, April 2013

Palaeolithic research where east meets west, Rodafnidia on Lesvos, NE Aegean Sea, Ν. Galanidou, J. McNabb, G. Iliopoulos, J. Cole, European Palaeolithic Conference, British Museum, London, February 2013

2012

Excavating Rodafnidia, an Acheulean open air-site on Lesvos, NE Aegean Sea, Ν. Galanidou, J. McNabb, G. Iliopoulos, J. Cole, Human Evolution in the Southern Balkans, University of Tübingen, Germany, December 2012